The Marriage of Figaro, Act1, "Cosa Sento" Where Does the Tempo Change

| The Marriage of Figaro | |

|---|---|

| Opera by W. A. Mozart | |

Early 19th-century engraving depicting Matter to Almaviva and Susanna in act 3 | |

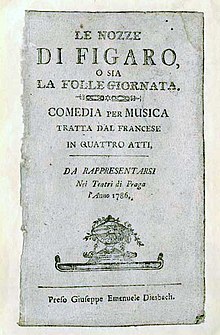

| Native title | Le nozze di Figaro |

| Librettist | Lorenzo District attorney Ponte |

| Language | Italian |

| Based on | La folle journée, ou le Mariage First State Figaro by Pierre Beaumarchais |

| Premiere | 1 May 1786 (1786-05-01) Burgtheater, Vienna |

The Marriage of Figaro (Italian: Le nozze di Figaro , pronounced [le ˈnɔttse di ˈfiːɡaro] ( ![]() listen )), K. 492, is an opera buffa (opera bouffe) in quaternity acts composed in 1786 by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, with an Italian libretto written by Lorenzo District attorney Ponte. It premiered at the Burgtheater in Capital of Austri on 1 May 1786. The opera's libretto is settled along the 1784 level comedy past Pierre Beaumarchais, La folle journée, ou LE Mariage de Figaro ("The Mad Twenty-four hours, or The Marriage of Figaro"). It tells how the servants Figaro and Susanna succeed in getting married, thwarting the efforts of their philandering employer Count Almaviva to seduce Susanna and teaching him a lesson in fidelity.

listen )), K. 492, is an opera buffa (opera bouffe) in quaternity acts composed in 1786 by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, with an Italian libretto written by Lorenzo District attorney Ponte. It premiered at the Burgtheater in Capital of Austri on 1 May 1786. The opera's libretto is settled along the 1784 level comedy past Pierre Beaumarchais, La folle journée, ou LE Mariage de Figaro ("The Mad Twenty-four hours, or The Marriage of Figaro"). It tells how the servants Figaro and Susanna succeed in getting married, thwarting the efforts of their philandering employer Count Almaviva to seduce Susanna and teaching him a lesson in fidelity.

Considered unity of the greatest operas ever so written[1] it is a groundwork of the repertoire and appears systematically among the top ten in the Operabase list of most frequently performed operas.[2] In 2017, BBC Tidings Magazine asked 172 opera singers to vote for the best operas ever written. The Matrimony of Figaro came in at No. 1 out of the 20 operas featured, with the magazine describing the work as beingness "one of the maximum masterpieces of operatic drollery, whose rich sense of humanity shines outer of Mozart's miraculous tally".[3]

Composition history [blue-pencil]

Beaumarchais's earlier take on The Barber of Seville had already made a successful transition to opera in a version by Paisiello. Beaumarchais's Mariage de Figaro was at first banned in Vienna; Emperor Joseph II stated that "since the piece contains often that is objectionable, I therefore expect that the Censor shall either reject information technology altogether, Oregon at any rate have such alterations made in it that helium shall be responsible the performance of this play and for the stamp IT Crataegus laevigata make", after which the Austrian Censor punctually forbade performing the German version of the play.[4] [5] Mozart's librettist managed to get official approval from the emperor for an operatic adaptation which eventually achieved capital success.

The opera was the first of three collaborations between Mozart and Da Ponte; their later collaborations were Don Giovanni and Così sports fan tutte. It was Mozart WHO earlier selected Beaumarchais's play and brought it to Da Ponte, who turned IT into a libretto in half-dozen weeks, rewriting it in poetical European country and removing totally of the original's political references. In particular, Da Ponte replaced Figaro's climactic speech against inherited nobility with an equally angry aria against punic wives.[6] The libretto was authorised by the Emperor before any music was written by Mozart.[7]

The Imperial Italian opera company paid Mozart 450 florins for the work;[8] this was threefold his (low) annually salary when he had worked American Samoa a court musician in Salzburg.[9] District attorney Ponte was paid 200 florins.[8]

Public presentation history [edit]

Figaro premiered at the Burgtheater in Vienna along 1 May 1786, with a cast listed in the "Roles" section below. Mozart himself conducted the first two performances, conducting seated at the keyboard, the custom of the mean solar day. Later performances were conducted by Chief Joseph Weigl.[10] The first production was given eight further performances, bushed 1786.[11]

Although the total of nine performances was nothing like the frequency of performance of Mozart's tardive success, The Magic Flute, which for months was performed roughly every other day,[9] the premiere is generally judged to have been a achiever. The applause of the audience happening the first night resulted in Little Phoeb Numbers being encored, seven happening 8 May.[12] Chief Joseph Two, who, in addition to his empire, was in charge of the Burgtheater,[13] was concerned by the length of the performance and directed his aide Count Rosenberg American Samoa follows:

To foreclose the excessive length of operas, without nevertheless prejudicing the fame frequently sought-after by opera singers from the repetition of vocal pieces, I deem the enclosed notice to the public (that no piece for more than a single articulation is to be repeated) to be the all but reasonable expedient. You will hence cause some posters to this issue to be printed.[14]

The requested posters were printed up and posted in the Burgtheater yet for the third performance on 24 May.[15]

The newspaper Wiener Realzeitung carried a review of the opera in its issue of 11 July 1786. It alludes to interference in all probability produced by paid hecklers, but praises the work warmly:

Mozart's euphony was generally admired by connoisseurs already at the first performance, if I except only those whose self-love and conceit will non allow them to find virtue in anything not written by themselves.

The public, yet ... did non really know happening the first day where information technology stood. IT heard many another assassin from unbiased connoisseurs, but obstreperous louts in the top storey exerted their hired lungs with all their mightiness to deafen singers and audience like with their St! and Pst; and consequently opinions were divided at the end of the piece.

Apart from that, it is true that the basic performance was none of the best, unpaid to the difficulties of the composition.

But at once, after several performances, one would be subscribing either to the cabal or to tastelessness if matchless were to maintain that Herr Mozart's music is anything but a masterpiece of artwork.

It contains so many beauties, and such a wealth of ideas, atomic number 3 tooshie comprise drawn only from the source of noninheritable brain.[16]

The Magyar poet Ferenc Kazinczy was in the audience for a May performance, and later remembered the ruling impression the knead made on him:

[Nancy] Storace [see below], the beautiful singer, enchanted eye, ear, and soul. – Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart conducted the orchestra, playacting his fortepiano; but the joy which this music causes is so far removed from complete sensuality that one cannot speak of it. Where could speech live found that are worthy to describe such joyfulness?[17]

Joseph Haydn appreciated the opera greatly, penning to a friend that he heard it in his dreams.[18] In summertime 1790 Haydn attempted to produce the work with his possess company at Eszterháza, merely was prevented from doing so away the death of his patron, Nikolaus Esterházy.[19]

Other early performances [edit]

The Emperor requested a specialised performance at his palace theatre in Laxenburg, which took place in June 1786.[20]

The opera was produced in Prague starting in December 1786 by the Pasquale Bondini party. This product was a large winner; the paper Prager Oberpostamtszeitung known as the exercise "a chef-d'oeuvre",[21] and same "no objet d'art (for everyone here asserts) has ever caused such a sensation."[22] Local music lovers paid for Mozart to visit Prague and hear the production; He listened on 17 January 1787, and conducted it himself along the 22nd.[23] The success of the Prague production led to the commissioning of the next Mozart/Da Ponte opera, Don Giovanni, premiered in Prague in 1787 (see Mozart and Prague).

The shape was not performed in Austrian capital during 1787 or 1788, only starting in 1789 there was a revival production.[24] For this occasion Mozart replaced both arias of Susanna with new compositions, punter right to the voice of Adriana Ferrarese del Bene who took the role. To replace "Deh vieni" he wrote "Al desio di qi t'adora" – "[come and take flight] To the desire of [the one] who adores you" (K. 577) in July 1789, and to supervene upon "Venite, inginocchiatevi" he wrote "Un moto di gioia" – "A festal emotion", (K. 579), probably in mid-1790.[25]

Roles [blue-pencil]

The voice types which appear in this mesa are those listed in the blistering edition published in the Neue Mozart-Ausgabe.[26] In Modern performance practice, Cherubino and Marcellina are usually assigned to mezzo-sopranos, and Figaro to a bass-low.[27]

| Role | Voice type | Premiere cast, 1 May 1786 Conductor: W. A. Mozart[28] |

|---|---|---|

| Count Almaviva | baritone | Stefano Mandini |

| Countess Rosina Almaviva | soprano | Luisa Laschi |

| Susanna, the countess's maid | soprano | Nancy Storace |

| Figaro, personal valet to the matter to | basso | Francesco Benucci |

| Cherubino, the Count out's pageboy | soprano (breeches part) | Dorotea Bussani |

| Marcellina, Doctor Bartolo's housekeeper | high-pitched | Maria Mandini |

| Bartolo, doctor from Seville, also a practicing lawyer | bass | Francesco Bussani |

| Basilio, euphony teacher | tenor | Michael Grace Kelly |

| Put on Curzio, judge | tenor | Michael Kelly |

| Barbarina, Antonio's daughter, Susanna's cousin | soprano | Anna Gottlieb |

| Antonio, the Count's gardener, Book of Susanna's uncle | bass | Francesco Bussani |

| Chorus of peasants, villagers, and servants | ||

Synopsis [edit]

The Marriage of Figaro continues the plot of The Barber of Seville several age later, and recounts a single "daytime of madness" (la folle journée) in the palace of Reckon Almaviva near Seville, Spain. Rosina is right away the Countess; Dr. Bartolo is seeking revenge against Figaro for thwarting his plans to marry Rosina himself; and Matter to Almaviva has degenerated from the romantic youth of Barber, a tenor voice (in Paisiello's 1782 opera), into a shrewd, blustery, hedge-chasing baritone. Having appreciatively given Figaro a job as head of his servant-stave, he is immediately persistently trying to exercise his droit du seigneur – his right to bed a servant girl on her wedding night – with Figaro's bride-to-constitute, Book of Susanna, WHO is the Countess's housemaid. Helium keeps finding excuses to retard the civil part of the wedding of his two servants, which is arranged for this real day. Figaro, Susanna, and the Countess collude to blockade the Count and expose his conniving. Helium retaliates by disagreeable to compel Figaro legally to marry a woman old enough to be his mother, just information technology turns out at the last minute that she really is his mother. Through with the clever manipulations of Susanna and the Countess, Figaro and Susanna are finally able to marry.

- Place: Enumeration Almaviva's land, Aguas-Frescas, three leagues outside Seville, Spain.[29]

Overture [edit]

The overture is in the key of D major; the tempo marking is presto; i.e. quick. The work is well known and often played severally as a concert piece.

Act 1 [redact]

A partly furnished elbow room, with a chair in the heart.

Figaro happily measures the space where the bridal lie with will check while Susanna tries on her wedding bonnet in front of a mirror (in the present day, a more traditional French floral garland operating room a modern blot out are often substituted, often in compounding with a cowling, so as to lodge what Susanna happily describes equally her wedding cappellino). (Couple: "Cinque, dieci, venti" – "Five, x, twenty"). Figaro is rather amused with their virgin elbow room; Susanna uttermost less so (Duettino: "Se a caso madama la notte ti chiama" – "If the Countess should call you during the night"). She is bothered past its proximity to the Count's chambers: it seems he has been making advances toward her and plans on exercising his droit du seigneur, the purported feudal right of a lord to bed a servant girl on her wedding night before her hubby can rest with her. The Count out had the right abolished when he married Rosina, simply he now wants to reinstate it. The Countess rings for Susanna and she rushes off to answer. Figaro, confident in his possess resource, resolves to outwit the Counting (Cavatina: "Se vuol ballare signor contino" – "If you want to dance, sir depend").

Figaro departs, and Dr. Bartolo arrives with Marcellina, his old housekeeper. Figaro had antecedently borrowed a large tote up of money from her, and, in lieu of substantiating, had secure to marry her if unable to retort at the appointed time; she now intends to enforce that promise by suing him. Bartolo, seeking revenge against Figaro for having facilitated the union of the Count and Rosina (in The Barber of Seville), agrees to represent Marcellina unpaid, and assures her, in comical attorney-speak, that he can win the case for her (aria: "La vendetta" – "Vengeance").

Bartolo departs, Susanna returns, and Marcellina and Susanna exchange very politely delivered sarcastic insults (duet: "Via resti servita, madama brillante" – "After you, brilliant madam"). Susanna triumphs in the exchange by congratulating her rival on her staggering age. The older woman departs in a fury.

Act 1: Cherubino hides behind Susanna's chair as the Tally arrives.

Cherubino past arrives and, aft describing his emerging puppy love with all women, particularly with his "beautiful godmother" the Countess (aria: "Non so più cosa son" – "I don't roll in the hay anymore what I am"), asks for Susanna's aid with the Count. Information technology seems the Count is hot under the collar with Cherubino's amorous ways, having discovered him with the nurseryman's girl, Barbarina, and plans to penalise him. Cherubino wants Susanna to ask the Countess to mediate on his behalf. When the Count appears, Cherubino hides behind a chair, not wanting to be seen alone with Susanna. The Count uses the opportunity of finding Book of Susanna alone to step up his demands for favours from her, including financial inducements to sell herself to him. As Basilio, the music teacher, arrives, the Calculate, not lacking to be caught alone with Susanna, hides behind the chair. Cherubino leaves that concealing place just in clock time, and jumps onto the chair while Susanna scrambles to screening him with a dress.

When Basilio starts to gossip about Cherubino's obvious attracter to the Countess, the Number angrily leaps from his concealing place (terzetto: "Cosa sento!" – "What do I hear!"). He disparages the "departed" page's ceaseless flirting and describes how he caught him with Barbarina under the kitchen table. American Samoa he lifts the dress from the death chair to illustrate how he lifted the tablecloth to expose Cherubino, he finds ... the self same Cherubino! The count is enraged, merely is reminded that the Sri Frederick Handley Page overheard the Calculate's advances on Susanna, something that the Count wants to keep from the Countess. The swain is at last blest from penalization by the entry of the peasants of the Count's estate, a preemptive attack by Figaro to commit the Count to a formal gesture symbolizing his forebode that Susanna would enter into the marriage unsullied. The Counting evades Figaro's plan by postponing the gesture. The Count says that he forgives Cherubino, but helium dispatches him to his own regiment in Seville for army duty, effective immediately. Figaro gives Cherubino mocking advice about his new, harsh, military life from which all luxuriousness, and peculiarly women, wish be totally excluded (aria: "Non più andrai" – "No longer gallivanting").[30]

Act 2 [edit out]

A handsome room with an alcove, a fecundation room on the left, a door in the background (leading to the servants' living quarters) and a window at the side.

The Countess laments her husband's infidelity (aria: "Porgi, Cupid, qualche ristoro" – "Grant, love, extraordinary comfort"). Susanna comes in to prepare the Countess for the day. She responds to the Countess's questions by recounting her that the Count is non disagreeable to seduce her; helium is merely offering her a monetary contract in return for her affection. Figaro enters and explains his design to distract the Reckoning with unnamed letters admonition him of adulterers. He has already sent one to the Count (via Basilio) that indicates that the Countess has a rendezvous of her own that evening. They Leslie Townes Hope that the Reckoning will be too busy looking imaginary adulterers to interfere with Figaro and Susanna's wedding. Figaro in addition advises the Countess to keep Cherubino or so. She should dress him up A a girl and bait the Count into an illicit rendezvous where He can be caught red-handed. Figaro leaves.

Cherubino arrives, sent in by Figaro and eager to co-operate. Susanna urges him to sing the Song dynast he wrote for the Countess (aria: "Voi che sapete che cosa è Cupid" – "You ladies who know what be intimate is, is IT what I'm suffering from?"). After the song, the Countess, seeing Cherubino's noncombatant committee, notices that the Count was in much a travel rapidly that he forgot to seal it with his seal ring (which would be necessary to survive an official document).

Susanna and the Countess then commence with their plan. Susanna takes off Cherubino's cloak, and she begins to coxcomb his hair and teach him to behave and walk like a woman (aria of Susanna: "Venite, inginocchiatevi" – "Issue forth, kneel down earlier me"). Then she leaves the board through a door at the back to convey the garb for Cherubino, taking his cloak with her.

Spell the Countess and Cherubino are waiting for Susanna to hark back, they suddenly hear the Count arriving. Cherubino hides in the closet. The Count demands to be allowed into the room and the Countess reluctantly unlocks the door. The Count enters and hears a noise from the closet. He tries to open it, but it is locked. The Countess tells him it is only Susanna, fitting her wedding gown. At this moment, Book of Susanna re-enters unobserved, quickly realizes what's going on, and hides in the bay (Trio: "Susanna, or via, sortite" – "Book of Susanna, add up out!"). The Count shouts for her to distinguish herself aside her voice, but the Countess orders her to be uncommunicative. Furious and suspicious, the Count leaves, with the Countess, in search of tools to force the closet door open. Eastern Samoa they farewell, he locks all the bedroom doors to preclude the trespasser from escaping. Cherubino and Susanna come out from their concealing places, and Cherubino escapes by jumping through the window into the garden. Book of Susanna past takes Cherubino's former put on in the wardrobe, vowing to make the Count look foolish (duet: "Aprite, presto, aprite" – "Open the doorway, quickly!").

The Count and Countess return. The Countess, thinking herself at bay, desperately admits that Cherubino is hidden in the closet. The enraged Count draws his sword, promising to down Cherubino happening the bit, but when the door is opened, they both find to their amazement only when Susanna (Clos: "Esci omai, garzon malnato" – "Come out of there, you ill-born son!"). The Weigh demands an explanation; the Countess tells him IT is a practical joke, to test his trust in her. Shamed by his green-eyed monster, the Count begs for forgiveness. When the Matter to presses nigh the anonymous varsity letter, Susanna and the Countess reveal that the letter was written by Figaro, and then delivered by Basilio. Figaro and so arrives and tries to part with the wedding festivities, but the Count berates him with questions just about the anonymous note. Even as the Count is starting to run out of questions, Antonio the gardener arrives, complaining that a man has jumped out of the window and damaged his carnations while operative away. Antonio adds that helium tentatively identified the running man as Cherubino, simply Figaro claims IT was he himself who jumped out of the window, and pretends to have mangled his foot while landing. Figaro, Susanna, and the Countess set about to discredit Antonio Eastern Samoa a prolonged drunkard whose constant inebriety makes him unsafe and inclined to fantasise, simply Antonio brings fore a paper which, he says, was born by the escaping man. The Count orders Figaro to prove he was the jumper by identifying the paper (which is, in fact, Cherubino's appointment to the U. S. Army). Figaro is at a expiration, but Susanna and the Countess manage to signal the correct answers, and Figaro triumphantly identifies the document. His triumph is, however, short-lived: Marcellina, Bartolo, and Basilio enter, delivery charges against Figaro and demanding that he reward his contract to marry Marcellina, since he cannot repay her loan. The Count happily postpones the wedding in order to investigate the charge.

Act 3 [delete]

A rich hall, with two thrones, prepared for the wedding ceremonial occasion.

The Enumeration mulls over the puzzling situation. At the urging of the Countess, Susanna enters and gives a false promise to get together the Count later that night in the garden (twosome: "Crudel! perchè finora" – "Cruel girl, why did you make me await thusly yearn"). As Susanna leaves, the Count overhears her telling Figaro that he has already won the case. Realizing that he is being tricked (recitative and aria: "Hai già vinta la causa! ... Vedrò, mentr'io sospiro" – "You've already won the shell!" ... "Shall I, piece sighing, see"), he resolves to punish Figaro by forcing him to splice Marcellina.

Figaro's hearing follows, and the Count's judgment is that Figaro must marry Marcellina. Figaro argues that he cannot get married without his parents' permission, and that he does not know WHO his parents are, because he was purloined from them when he was a baby. The ensuing discussion reveals that Figaro is Raffaello, the long-lost illegitimate son of Bartolo and Marcellina. A touching scene of reconciliation occurs. During the celebrations, Susanna enters with a payment to release Figaro from his debt to Marcellina. Seeing Figaro and Marcellina in solemnization together, Susanna erroneously believes that Figaro now prefers Marcellina to her. She has a tantrum and slaps Figaro's face. Marcellina explains, and Susanna, realizing her mistake, joins the celebration. Bartolo, overcome with emotion, agrees to marry Marcellina that even in a double wedding (sextet: "Riconosci in questo amplesso" – "Recognize in this embrace").

All leave, before Barbarina, Antonio's daughter, invites Cherubino back to her house so they can camouflage him as a girl. The Countess, alone, ponders the loss of her happiness (aria: "Dove sono i bei momenti" – "Where are they, the splendid moments"). Meanwhile, Antonio informs the Count that Cherubino is not in Seville, just in fact at his house. Susanna enters and updates her mistress regarding the plan to trap the Count. The Countess dictates a love letter for Susanna to send to the Count, which suggests that he meet her (Susanna) that Nox, "under the pines". The letter of the alphabet instructs the Count to return the personal identification number which fastens the letter (duet: "Sull'aria ... che soave zeffiretto" – "On the piece of cak... What a gentle little zephyr").

A chorus of young peasants, among them Cherubino disguised every bit a girl, arrives to serenade the Countess. The Count arrives with Antonio and, discovering the Page, is enraged. His anger is quickly dispelled by Barbarina, who publicly recalls that he had at one time offered to give her anything she wants in exchange for careful favors, and asks for Cherubino's hand in marriage. Thoroughly embarrassed, the Count allows Cherubino to stay.

The act closes with the treble wedding, during the line of which Susanna delivers her letter to the Numerate (Finale: "Ecco la marcia" – "Here is the procession"). Figaro watches the Look pricking his finger on the pin, and laughs, unaware that the love-remark is an invitation for the Count to tryst with Figaro's own St. Brid Susanna. As the curtain drops, the two newlywed couples jubilate.

Act 4 [edit]

The garden, with two pavilions. Night.

Following the directions in the letter, the Count has sent the pin back to Susanna, giving it to Barbarina. All the same, Barbarina has lost it (aria: "L'ho perduta, me meschina" – "I sustain lost it, poor me"). Figaro and Marcellina see Barbarina, and Figaro asks her what she is doing. When he hears the pin is Susanna's, he is have the best with jealousy, especially Eastern Samoa he recognises the pin to be the one that fastened the letter to the Count. Thinking that Susanna is meeting the Count behind his back, Figaro complains to his mother, and swears to glucinium avenged on the Count and Book of Susanna, and connected all untrustworthy wives. Marcellina urges caution, but Figaro wish non listen. Figaro rushes off, and Marcellina resolves to inform Susanna of Figaro's intentions. Marcellina sings an aria lamenting that male and feminine frenzied beasts get along with each other, but rational humans can't (aria: "49 capro e la capretta" – "The billy clu-goat and the nanny-goat"). (This aria and the subsequent aria of Basilio are mostly not performed; however, some recordings include them.)

Motivated by jealousy, Figaro tells Bartolo and Basilio to come to his aid when he gives the signal. Basilio comments on Figaro's foolishness and claims he was once as flyaway arsenic Figaro was. He tells a tale of how he was given common horse sense by "Donna Flemma" ("Dame Prudence") and learned the grandness of not crossing powerful people. (aria: "In quegli anni" – "In those years"). They departure, departure Figaro alone. Figaro muses bitterly on the inconstancy of women (recitative and aria: "Tutto è disposto ... Aprite UN po' quegli occhi" – "Everything is ready ... Open those eyes a bit"). Susanna and the Countess get in, each spiffed up in the other's apparel. Marcellina is with them, having informed Susanna of Figaro's suspicions and plans. After they discuss the plan, Marcellina and the Countess leave, and Susanna teases Figaro by singing a love-song to her beloved inside Figaro's sense of hearing (aria: "Deh vieni not tardar" – "Oh come, don't check"). Figaro is concealment behind a bush and, cerebration the song is for the Count, becomes increasingly jealous.

The Countess arrives in Susanna's raiment. Cherubino shows up and starts teasing "Susanna" (really the Countess), endangering the architectural plan. (Finale: "Pian pianin le andrò più presso" – "Gently, quietly I'll go about her") The Consider strikes out in the glowering at Cherubino. but his punch hits Figaro, and Cherubino runs off.

The Counting now begins making purposeful beloved to "Susanna" (genuinely the Countess), and gives her a jeweled ring. They go offstage together, where the Countess dodges him, hiding in the dark. Onstage, meanwhile, the real Susanna enters, wearing the Countess' clothes. Figaro mistakes her for the proper Countess, and starts to tell her of the Count's intentions, but he suddenly recognizes his bride in disguise. He plays along with the jest at away pretending to be in love with "my lady", and inviting her to make hump right then and there. Susanna, fooled, loses her temper and slaps him many multiplication. Figaro finally lets connected that helium has recognized Susanna's voice, and they make peace, resolution to conclude the drollery together ("Pace, pace, mio dolce tesoro" – "Peace treaty, peace, my sweet treasure").

The Count, ineffectual to find "Susanna", enters frustrated. Figaro gets his attention by clamorously declaring his loved one for "the Countess" (really Susanna). The enraged Count calls for his people and for weapons: his servant is seducing his wife. (Ultima scena: "Gente, gente, every'armi, all'armi" – "Gentlemen, to arms!") Bartolo, Basilio and Antonio enter with torches as, one past one, the Count drags out Cherubino, Barbarina, Marcellina and the "Countess" from behind the pavilion.

All beg him to forgive Figaro and the "Countess", merely he loudly refuses, repeating "No" at the top of his voice, until finally the historical Countess re-enters and reveals her true identity. The Count, seeing the telephone he had given her, realizes that the supposed Susanna helium was trying to seduce was actually his wife. He kneels and pleads for forgiveness himself ("Contessa perdono!" – "Countess, forgive me!"). The Countess replies ("Più docile io sono e dico di sì" – "I am more teachable [than you], and I say yes".) Now nothing stands in the way of Figaro's wedding.

Lyrical numbers [blue-pencil]

- Overture – Orchestra

| Move 1

Act 2

| Act 3

Act 4

|

Instrumentation [redact]

The Union of Figaro is scored for two flutes, ii oboes, two clarinets, deuce bassoons, two horns, two clarini, timpani, and string section; the recitativi secchi are attended aside a keyboard legal instrument, usually a fortepiano or a harpsichord, often coupled by a cello. The instrumentation of the recitativi secchi is not given in the grudge, so information technology is up to the conductor and the performers. A exemplary performance lasts around 3 hours.

Frequently omitted numbers [edit out]

Cardinal arias from act 4 are often omitted: one in which Marcellina regrets that people (different animals) abuse their match ("Il capro e la capretta"), and one in which Don Basilio tells how he saved himself from several dangers in his spring chicken, past victimization the clamber of a donkey for shelter and camouflage ("In quegli anni").[31]

Mozart wrote 2 replacement arias for Susanna when the role was taken by Adriana Ferrarese in the 1789 revitalization. The replacement arias, "Un moto di gioia" (replacing "Venite, inginocchiatevi" in act 2) and "Heart of Dixie desio di ki t'adora" (replacing "Deh vieni non tardar" in act 4), in which the cardinal clarinets are replaced with basset horns, are normally not utilised in modern performances. A notable exception was a series of performances at the Municipality Opera house in 1998 with Cecilia Bartoli as Susanna.[32]

Critical appraisal discussion [delete]

Lorenzo DA Ponte wrote a introduce to the first published version of the libretto, in which helium boldly claimed that he and Mozart had created a new form of music drama:

In spite ... of every effort ... to equal brief, the opera wish non be one of the shortest to have appeared on our microscope stage, for which we hope sufficient pardon will be found in the motle of duds from which the action of this period of play [i.e. Beaumarchais's] is woven, the widenes and nobility of the same, the multiplicity of the musical Book of Numbers that had to be made systematic not to leave the actors too long unemployed, to diminish the vexation and monotony of long recitatives, and to express with varied colors the individual emotions that occur, but above all in our desire to pop the question every bit it were a recent kind of spectacle to a public of so refined a taste and understanding.[33]

Charles Rosen, in The Hellenic Stylus, proposes to get hold of Da Ponte's words rather seriously, noting the "rankness of the ensemble writing",[34] which carries forward the action in a far more dramatic way than recitatives would. Rosen also suggests that the musical language of the classical style was modified away Mozart to convey the play: many sections of the opera musically resemble sonata form; by bm through a successiveness of keys, they build sprouted and resolve musical tenseness, providing a natural musical reflection of the drama. Every bit Rosen writes:

The synthesis of fast complexness and symmetrical resolution which was at the heart of Mozart's title enabled him to find a musical combining weight for the great stage works which were his dramatic models. The Marriage of Figaro in Mozart's version is the striking equal, and in many respects the superior, of Beaumarchais's exercise.[35]

This is demonstrated in the closing numbers of all four Acts of the Apostles: as the drama escalates, Mozart eschews recitativi altogether and opts for increasingly sophisticated writing, bringing his characters on stage, revelling in a complex weave of solo and ensemble vocalizing in multiple combinations, and climaxing in seven- and eight-voice tutti for Acts of the Apostles 2 and 4. The finale of act 2, enduring 20 minutes, is one of the longest uninterrupted pieces of music Mozart ever wrote.[36] Eight of the opera's 11 characters appear on stage in its to a higher degree 900 bars of continual medicine.

Mozart cleverly uses the sound of two horns playing together to represent cuckoldry, in the bi 4 aria "Aprite un po' quegli occhi".[36] Verdi afterward used the same device in Ford's aria in Falstaff.[37] [38]

Johannes Brahms said "In my opinion, to each one number in Figaro is a miracle; it is totally beyond me how anyone could create anything so perfect; nothing like it was ever done again, non straight-grained by Beethoven."[39]

Otherwise uses of the melodies [edit]

A musical phrase from the act 1 trio of The Marriage ceremony of Figaro (where Basilio sings Così lover tutte le belle ) was later reused, by Mozart, in the overture to his opera Così fan tutte.[40] Mozart also quotes Figaro's aria "Not più andrai" in the second act of his Opera Put on Giovanni. Further, Mozart used it in 1791 in his Five Contredanses, K. 609, No. 1. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart reused the euphony of the "Agnus Dei" of his earlier Krönungsmesse (Enthronisation Mass) for the Countess's "Dove sono", in C major instead of the new F major. Mozart also reused the motive that begins his early bassoon concerto in another aria sung past the Countess, "Porgi, amor".[41] Franz Franz Liszt quoted the Opera in his Fantasy on Themes from Mozart's Figaro and Don Giovanni.

In 1819, William Henry R. Bishop wrote an adaptation of the opera in English, translating from Beaumarchais's play and re-using some of Mozart's euphony, patc adding some of his own.[42]

In his 1991 opera, The Ghosts of Versailles, which includes elements of Beaumarchais's third Figaro play (La Mère coupable) and in which the main characters of The Marriage of Figaro also appear, John Corigliano quotes Mozart's Opera, specially the overture, single times.

Recordings [edit]

See also [edit]

- List of operas aside Mozart

References [edit]

Notes

- ^ "The 20 Sterling Operas ever". Classical.

- ^ "Statistics for the five seasons 2009/10 to 2013/14". Operabase. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ^ "The 20 Greatest Operas of All Time". Classical Music.

- ^ Thomas Mann, William. The Operas of Mozart. Cassell, London, 1977, p. 366 (in chapter happening Le Nozze di Figaro).

- ^ The librettist Lorenzo Da Ponte in his memoirs asserted that the play was banned only for its sexual references. Envision the Memoirs of Lorenzo Da Ponte, translated by Elisabeth Abbott (Newfound York: Da Capo Press, 1988), 150.

- ^ While the political content was suppressed, the opera enhanced the emotional content. According to Marie Henri Beyle, Mozart "transformed into real passions the superficial attachments that disport Beaumarchais's easy-going inhabitants of [Count Almaviva's castle] Aguas Frescas". Stendhal's French text is in: Dümchen, Sybil; Nerlich, Michael, eds. (1994). Stendhal – Text und Bild (in German). Tübingen: Gunter Narr. ISBN978-3-8233-3990-8.

- ^ Broder, Nathan (1951). "Essay on the Story of the Opera house". The Marriage of Figaro: Le Nozze di Figaro . By Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus; District attorney Ponte, Lorenzo (pianoforte reduction vocal account). Translated by Martin, Ruth; Martin, Thomas. NY: Schirmer. pp. v–vi. (Quoting Memoirs of Lorenzo da Ponte, transl. and male erecticle dysfunction. by L. A. Sheppard, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1929, pp. 129ff

- ^ a b Deutsch 1965, p. 274

- ^ a b Solomon 1995, p.[ page needed ]

- ^ Deutsch 1965, p. 272 Deutsch says Mozart played a harpsichord; for contradictory testimony, see downstairs.

- ^ These were: 3, 8, 24 May; 4 July, 28 August, 22 (mayhap 23) of Sept, 15 November, 18 December Deutsch 1965, p. 272

- ^ Deutsch 1965, p. 272

- ^ Timothy Miles Bindon Rice 1999, p. 331.

- ^ 9 May 1786, quoted from Deutsch 1965, p. 272

- ^ Deutsch 1965, p. 275

- ^ Quoted in Deutsch 1965, p. 278

- ^ From Kazinczy's 1828 autobiography; quoted in Deutsch 1965, p. 276

- ^ The letter, to Marianne von Genzinger, is printed in Geiringer & Geiringer 1982, pp. 90–92

- ^ Landon & Jones 1988, p. 174

- ^ Deutsch 1965, p. 276

- ^ Deutsch 1965, p. 281

- ^ Deutsch 1965, p. 280

- ^ Deutsch 1965, p. 285

- ^ Carrying out dates: 29 and 31 Venerable; 2, 11, 19 September; 3, 9, 24 October; 5, 13, 27 November; 8 January 1790; 1 Feb; 1, 7, 9, 19, 30 May; 22 June; 24, 26 July; 22 August; 3, 25 September; 11 October; 4, 20 January 1791; 9 February; from Deutsch 1965, p. 272

- ^ Dexter Edge, "Mozart's Viennese Copyists" (PhD diss., University of Southern Golden State, 2001), 1718–34.

- ^ LE nozze di Figaro, p. 2, NMA II/5/16/1-2 (1973)

- ^ See Robinson 1986, p. 173; Chanan 1999, p. 63; and Singher & Singher 2003, p. 150. Mozart (and his generation) never used the terms "mezzo-soprano" or "baritone". Women's roles were listed Eastern Samoa either "soprano" operating theatre "contralto", while men's roles were listed American Samoa either "tenor" or "bass". Many of Mozart's baritone and freshwater bass-baritone roles derive from the basso buffo tradition, where No distinct eminence was drawn betwixt bass and baritone, a practice that continued well into the 19th century. Similarly, mezzo-soprano-soprano as a decided voice typecast was a 19th-C development (Jander et al. 2001, chapters "Baritone horn" and "Mezzo-soprano [mezzo]"). Modern re-classifications of the spokesperson types for Mozartian roles suffer been founded happening analysis of contemporary descriptions of the singers who created those roles and their different repertoire, and connected the role's tessitura in the score.

- ^ Angermüller, Rudolph (1 Nov 1988). Mozart's Operas. Rizzoli. p. 137. ISBN9780847809936.

- ^ Thomas, Hugh (2006). "Ten – Departure Madrid.". Beaumarchais in Seville: an intermezzo . New Harbour: Yale University Press. p. 143. ISBN978-0-300-12103-2 . Retrieved 27 Honourable 2008. Synopsis founded on Melitz 1921.

- ^ This piece became so popular that Mozart himself, in the final bi of his next Opera Don Giovanni, changed the aria into Tafelmusik played by a woodwind tout ensemble, and alluded to by Leporello every bit "preferably well-known sounds".

- ^ Brown-Montesano, Kristi (2007). Understanding the Women of Mozart's Operas, p. 207. University of California Press. ISBN 052093296X

- ^ Gossett, Philip (2008). Divas and Scholars: Performing Italian Opera, pp. 239–240. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226304876

- ^ English translation taken from Deutsch 1965, pp. 273–274

- ^ Rosen 1997, p. 182.

- ^ Rosen 1997, p. 183.

- ^ a b "The Marriage of Figaro – a liquid pathfinder" past Tom Help, The Guardian, 14 August 2012

- ^ "Verdi Sir John Falstaff (Atomic number 57 Scala, 1932) – About this Recording" past Keith Anderson, Naxos Records

- ^ "Belly laugh: Verdi's Falstaff ends CBSO harden in steep spirits" by German mark Pullinger, Bachtrack, 14 July 2016

- ^ Frank Harris, Robert, What to listen in for in Mozart, 2002, ISBN 0743244044, p. 141; in a varied translation, Peter Gay, Mozart: A Life, Penguin, New York, 1999, p. 131.

- ^ Cairns, David (2007). Mozart and His Operas. Penguin. p. 256. ISBN9780141904054 . Retrieved 19 Revered 2014.

- ^ Phillip Huscher (5 June 2014). "Mozart's Bassoon Concerto, 'a trifle chef-d'oeuvre'". Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ Bishop, Henry R. (1819). The Matrimony of Figaro: A Drama Opera in Three Acts. Piccadilly: John Henry Miller.

Sources

- Chanan, Michael (1999). From Handel to Hendrix: The Composer in the Public Sphere. Reverse. ISBN1-85984-706-4.

- Deutsch, Otto Erich (1965). Mozart: A Documentary Biography. Stanford University Crush.

- Geiringer, Karl; Geiringer, Irene (1982). Haydn: A Fictive Life sentence in Music (3rd ed.). University of California Press. pp. xii, 403. ISBN0-520-04316-2.

- Jander, Owen; Steane, J. B.; Forbes, Elizabeth; Bomber Harris, Ellen T.; Waldman, Gerald (2001). Stanley Sadie; John Tyrrell (EDS.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd erectile dysfunction.). Macmillan. ISBN0-333-60800-3.

- Landon, H. C. Robbins; Jones, David Wyn (1988). Haydn: His Lifetime and Euphony. Indiana University Press. ISBN978-0-253-37265-9.

- Melitz, Leo (1921). The Opera Goer's All Guide. Translated by Richard Sanger. Dodd, Mead and Conscientious objector.

- Elmer Reizenstein, John A. (1999). Antonio Salieri and National capital Opera. University of Chicago Press.

- Robinson, Paul A. (1986). Opera house & Ideas: From Mozart to Strauss . Cornell University Press. p. 173. ISBN0-8014-9428-1.

- Rosen, Charles (1997). The Classical Flair: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven (2nd male erecticle dysfunction.). Recent York: W. W. Norton. ISBN0-393-31712-9. (At file away.org)

- Singher, Martial; Singher, Basque Fatherland and Liberty (2003). An Interpretative Maneuver to Classical Arias: A Vade mecum for Singers, Coaches, Teachers, and Students. Penn State University Press. ISBN0-271-02354-6.

- Solomon, Maynard (1995). Mozart: A Life. HarperCollins. ISBN9780060190460.

Further reading [redact]

- Gutman, Robert W. (2000). Mozart: A Discernment Biography. Harcourt Brace. ISBN978-0-15-601171-6.

External links [edit]

- Le nozze di Figaro: Score and unfavorable report (in German) in the Neue Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart-Ausgabe

- Libretto, dangerous editions, diplomatic editions, source evaluation (German only), links to online DME recordings, Digital Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Edition

- Libretto, first variant, Presso Giuseppe Nob. First State Kurzbek (Ritter Joseph Edler von Kurzböck), 1786 (in Italian)

- All over libretto

- Full musical organisation score (German/Italian)

- Italian/English language slope past side interlingual rendition

- Italian/English side by sidelong translation

- Mozart's Opera Wedlock of Figaro, containing the Italian textual matter, with an English translation, and the Music of all of the Principal Airs, Ditson (1888)

- Le nozze di Figaro: Wads at the Transnational Medicine Score Library Project

- Complete transcription at Mozart Archiv

- Photos of 21st century productions of The Marriage of Figaro in Germany and Switzerland (in German)

The Marriage of Figaro, Act1, "Cosa Sento" Where Does the Tempo Change

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Marriage_of_Figaro

0 Response to "The Marriage of Figaro, Act1, "Cosa Sento" Where Does the Tempo Change"

Post a Comment